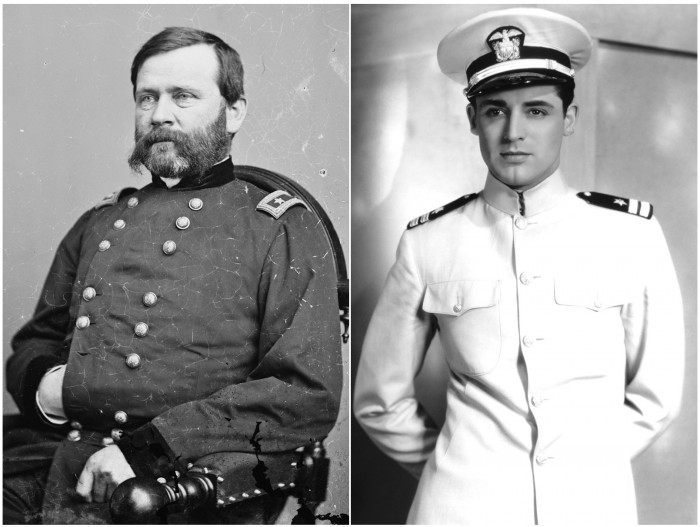

“On the hill opposite ours lived a little tea-house girl; her name was Chô-san, Miss Butterfly. She was so sweet and delicate that everyone was in love with her. In time we learned that she had a lover… quite nice, but very temperamental, of a moody, lonely disposition. One evening there was quite a sensation when it was learned that poor little Chô-san and her baby had been deserted. The man had promised to return at a certain time; had even arranged a signal so that Chô-san would know when his ship had come in; but the little girl-wife awaited that signal in vain. Many an hour and many a long night did she peer from her shoji over the lovely harbor, but to no purpose: He never returned.”

– Jennie Correll, as related in 1931

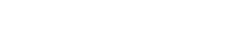

For 250 years, the island kingdom of Japan was sealed off from the world beyond her borders. Shipwrecked sailors from foreign lands were imprisoned or killed. Japanese ports were shut tightly to ships seeking to purchase coal or otherwise re-supply. As a result, Japan was considered mysterious and dangerous. But in the 19th century, the United States Navy began to eye Japan strategically. The U.S. had begun stocking their fleet with steamships—steamships that required coal. In the Pacific, Japan was the perfect location for U.S. ships to restock their coal supplies. Additionally, there was the intriguing possibility that, if properly groomed, Japan might develop into an exciting new trading partner.

Nagasaki Harbor circa 1880

On July 8, 1853, Commodore Matthew Perry steamed into Tokyo Bay on the U.S.S. Pawhatan, flanked by three more black ships. He carried a letter of greeting from the President of the United States. The Japanese had never seen steamboats, nor were they familiar with the vast array of guns these “smoking dragons” carried. Realizing that the kingdom could not risk war with this new power, the Japanese government entered into negotiations with Commodore Perry and on March 31, 1854, signed a treaty with the United States which guaranteed peace and friendship between the two nations, access to the ports of Shimoda and Hakodate, help for shipwrecked Americans, and permission for Americans to purchase supplies from Japan.

The opening of Japan was the first trickle in a floodgate of Japanese exoticism surging into the U.S. and Europe. Suddenly the West nurtured a fetishistic fascination for all things Japanese. Art, craft, music and theater all began to reflect this obsession, spurred on by the Centennial World’s Fair, to which the Japanese brought goods specifically designed for Western audiences. For nearly 50 years, the West continued its preoccupation with the mysterious “Orient,” and Puccini could not have helped being influenced by the japonisme of the 19th century. Certainly the libretto for Madame Butterfly is based upon literature heavily influenced by the movement.

The opera Madame Butterfly (1904) was based upon a play of the same title by David Belasco, which, in turn is based upon a short story by John Luther Long. Long contended his story was based upon actual events as related to him by his missionary sister, Jennie Correll, who spent years in Nagasaki, and knew not only many of the naval officers who put into port, but the local people, too. In 1931, she published her memoir of the story she told her brother, based on the transcript of a talk she gave earlier the same year. In addition to his sister’s story, Long almost certainly borrowed some elements from Pierre Loti’s semi-autobiographical novel, Madame Chrysanthème. The theme of the East-meets-West romance gone terribly wrong had flourished in the Western imagination since the 1885 publication of Loti’s book, and his description of the temporary “Japanese” marriage engaged in by foreign male visitors to Japan provided a useful basis of understanding for Chô-san’s tragic misunderstanding in Long’s literary version of his sister’s account. Judging by the shockingly intense and violent letters Long received from U.S. Navy officers protesting the book (“savage,” as he described them), even if his plot was not factually true, the situation described by the story was obviously a tad too true for comfort.

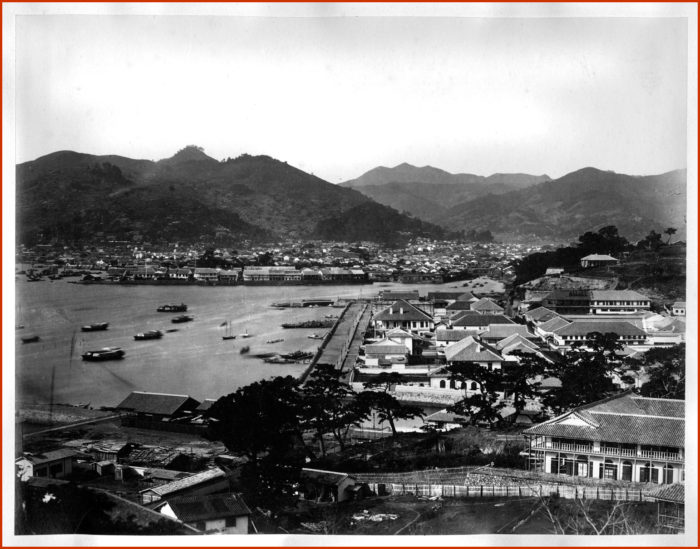

[L] William B. Franklin (the historical basis for Pinkerton): [R] Cary Grant as Pinkerton in the 1932 film version

Cornell Professor of Music Arthur Groos, in his 1991 article, Madame Butterfly: The Story, argues convincingly that the characters in Long’s story, and in Puccini’s subsequent opera, have historical corollaries. Certainly, the practice of “Japanese marriage,” (or “marriage-by-the-month”) existed and was widely documented. Groos’ research places the incidents Mrs. Correll describes between the years of 1892 and 1893, and he found Pinkerton thinly veiled in either a composite of Dr. John S. Sayre and William B. Franklin, or William B. Franklin alone. Groos feels strongly, however, that Pinkerton is separate from Sayre, and is cautiously convinced that dashing young Ensign William B. Franklin was the “temperamental” lover Jennie Correll described. Chô-san, as many women of her time, has been lost to history, and we know no more of her than Mrs. Correll’s description of her as “sweet and delicate.” Despite the true origins of the story, Long, Belasco and Puccini all added their own literary flourishes. Pinkerton’s American wife is certainly fictional, as is Pinkerton’s return to collect his son. Mrs. Correll states that no one returned for Chô-san or her child, and the most likely fate for them is described by Clara Whitney, a young woman living in Japan in 1875:

“Young men here are wicked and depraved and insult the gentle Japanese as often as they can. Merchants—married men—keep native women in their houses as wives without marriage. Sailors are even worse still, and it is pitiful to see the poor little half-caste children running around uncared for, as the Japanese regard them as unclean and their fathers don’t care.”

This scenario makes logical Belasco’s conclusion that Chô-san would prefer to commit seppuku and give up her child than shoulder the stigma facing her son in Japanese society.

In 1900, Puccini attended a performance of Belasco’s play in London. Despite his limited English, Puccini was entranced by the tragic tale of Chô-san, the naive geisha, and applied to Belasco for the rights. During his wait for permission to proceed, Puccini sent a copy of Long’s short story to his customary librettists, Luigi Illica and Giuseppe Giacosa, so that they could begin work at once. They structured the opera to include a “prelude” of Butterfly’s wedding not included in the play, and then three acts, the first and third of which were to take place in Butterfly’s “little house on the hill” and the second of which was to occur at the American Consulate in Nagasaki. Illica also favored the Long ending in which Butterfly survives seppuku and raises her own child. Puccini objected (as usual) to both Long’s ending (favoring the stark tragedy of the play) and to the structure (removing the consulate act and preferring an hour and a half second act). Puccini’s work was further delayed by a motor car accident which left him badly injured. His recovery was slowed by his diabetes, but he did manage to complete the opera in December 1903. Eventually, Butterfly premiered with an all-star cast in 1904.

It was a complete catastrophe.

The original Butterfly, Rosina Storchio

Puccini described it as a lynching. Catcalls, boos and hisses greeted Puccini’s deeply personal work, flaying the delicate story and making ridiculous the cataclysmic undoing of Cio-Cio-San. Such a stupendous shellacking of a Puccini opera seems incredible. He had already had tremendous success with Manon Lescaut, La bohème and Tosca. The public adored him; the cast was brilliant. How is it possible that Butterfly was such an utter failure? There are undoubtedly several contributing factors: excessive length, excessive anti-Western feeling, excessive audience desire to “put Puccini in his place,” but the most fascinating and delightfully tabloid explanation is sabotage. Though many biographers decline to name the saboteurs, the most logical suspect is Sonzogno, publisher and archrival of Puccini’s publisher, Casa Ricordi. Sonzogno’s entire stable (Leoncavallo, Cilea, Mascagni and Giordano) had produced their best and none had matched Ricordi’s powerhouse, Puccini. In Sonzogno’s eyes, a fourth triumph for Puccini (and consequently, Casa Ricordi) was unacceptable.

The horrific experience of that first night forced Puccini to withdraw the score and modify what he considered his masterwork. The opening night debacle and subsequent success in Brescia later that year has led to the succinct, if misleading, myth, that this second, revised edition was the final version, the spectacular success that catapulted Butterfly into the foundational canon of contemporary operatic performance practice. Nothing could be further from the truth. Puccini notoriously tinkered with his own works after their initial opening, and he was a savvy man of the theater. Whenever he had the opportunity to be at rehearsals of new productions of his work, he was there, and he often changed the score to suit both the producing organization and himself. With Butterfly, what have been described as distinct versions (because of the order and way in which they were published) were actually the slow evolution of Puccini’s masterpiece. Most remarkable is that most of the changes were cuts, some of which changed the characters and their motivations. Of all the characterizations affected by the cuts, Pinkerton’s was the most profound. The callousness and racism of the original character is efficiently excised by Puccini’s numerous cuts, leaving him looking weak, rather than boorish.

Whether the version we are accustomed to watching is Puccini’s definitive one, we Westerners remain transported by Madame Butterfly. Long, Belasco and Puccini have paid far more care to Butterfly’s precarious position than their contemporaries or history have done, and they have given a voice to many voiceless young women throughout history, battered by callousness and cultural indifference. Regardless of whether Madame Butterfly is factually or culturally accurate or not, it speaks to the truth of many broken relationships and lives. It is that truth that ensures that few eyes are dry at the final curtain of Madame Butterfly, and that all but the stoniest hearts break for Butterfly’s sorrow.

~ by Alexis Hamilton, courtesy of Portland Opera